I hadn’t been to Hilton Head in ten years; it was considerably more developed—and crowded—than the last time. It was lunch time when I drove down that long, busy only-highway-from-the-mainland, and the traffic going the other way, leaving for the weekend I supposed, was already backed up. Which puzzled me: why would you leave a resort island for the weekend? Where would you be going to, Pocotaligo? “Dear, I am SO bored with Nice. What say we fly to Somalia for the weekend?” Decided to grab a quick bite for lunch, and then have a nice dinner on the island to avoid the Friday afternoon traffic. Wrote myself a reminder to PLAN BETTER NEXT TIME.

The gallery, Low Country Art (lots of things are Low Country around here), was pretty far down the food chain from the Low Country Gallery in Beaufort. Prices topped out at about half of where they started at Mr. Collins’ establishment, and most pieces were attractively priced for tourists at $100 to $200. But the biggest difference was the humorous art, something that would have driven Jerome to rip off his tailored suit and replace it with sackcloth.

When I’d called to “schedule meetings with the galleries,” Jerome Collins had put me on the calendar; Low Country Art had informed me that “whoever is working will be more than happy to help you.” Fat chance—the saleslady hadn’t been there long enough to remember George Foster. Plus once she decided I wasn’t buying anything, she was reluctant to waste any more courtesy—obviously a commodity in short supply—on me. Of course they didn’t keep records that far back at the store, I’d have to contact the manager if I wanted that information, here was his card. “Sorry we couldn’t be more help.” I was more surprised that she didn’t choke on the word “sorry” than I was at the royal “we.”

I know this is hard to believe, but there are women who don’t like me. And a significant percentage of those take an immediate, robust disliking. About the same number as the Missy Piersons of the world who, at first sight, want to bear my children. I’ve adopted as the most likely explanation that it’s genetic, hard-wired deep in their subconscious minds, courtesy of their prehistoric ancestors. Some women want big, burly men who’re a touch thick-headed and whose bedroom techniques involve the modern-day equivalent of a club (Uh, what’s your sign, darlin’. Wow, I’m a Cancer. Wanna fuck?) but will drop everything to go slay that Wooly Mammoth, baby. It was good enough for their great-times-a-few-thousand-generations grandmothers, by the Spirit of the Great Cave Bear, it’s good enough for them. My appeal to those women is zilch. Unfortunately, it’s never discernible from the outside. They appear the same as normal women (using the term loosely) who might want to go out with me: right age range, correct number of arms and legs and breasts, meet my minimum standard of attractiveness (which isn’t all that high, compared with most men I know). So I’m always taken by surprise, but by now I’m never surprised.

That’s OK; what the hell would we have to talk about? Fortunately, there are plenty of women who prefer wit to hunting skills.

This trip was turning out to be a big fat waste. More hours stolen from my life and flushed down the toilet, with the theft not softened whatsoever by a hint of charm or even basic politeness. As it is not my nature to give up without a fight, I strolled through the store, channeling the artists for guidance. And La Voila! There in the back room was a half wall displaying paintings by local artist Lacey Simpson.

And yes, I realized it could have been mere coincidence. But Lacey isn’t that common a name, particularly for women here in the Deep South old enough to date George Foster. I was relatively confident I’d located his mystery girl friend.

Except of course the snotty saleswoman-from-hell (or saleswoman-from-Lascaux, where the cave paintings are, would be more apt) wouldn’t tell me anything about Lacey Simpson, much less give me a phone number. “I’m sorry, sir, we have a strict privacy policy to protect our artists.”

“Can you at least give me a hint about how old she is?”

“I’m sorry, sir, that would definitely be a violation of our policy.”

“Well, suppose I want to ask a question about one of her pieces?”

“If I am unable to provide the information you require, sir, I would contact her and relay the question to her.” She made it clear without words that she believed the chance of my asking an intelligent question that she didn’t know the answer to was about the same as my understanding the theory of General Relativity. Good thing it wasn’t raining in there: as turned up as her nose was, she’d drown from the water running into her nostrils.

Well, how many Lacey Simpsons could there be on Hilton Head? Good thing I was a newspaperman. It’d give me a something to do to kill the afternoon and avoid the traffic.

None, as it turns out. No listing in the phone book. Eight other galleries on the island hadn’t heard of her. The newspaper office was back on the mainland, and I couldn’t locate anyone over the phone who’d heard of me—absolutely shocking—or who was willing to help a stranger. Even Google, normally more omniscient than God, couldn’t help. All she provided was a mention in a short advertisement for the gallery I’d just been to and two fuzzy images of paintings I’d already seen.

Well, at least I had a last name. That was one step further than I’d been. The combination of that and a good meal would be sufficient to make the trip worthwhile.

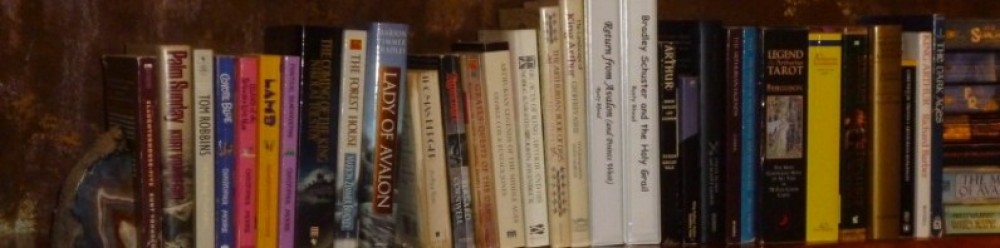

I ended up driving down to one of the public beaches—this late in the fall, it was abandoned by all but a few desultory surfers in wet suits hoping for a wave bigger than three feet, a couple of fanatics casting out into the surf, and two couples who cared more about their own emotional entanglements than the charm of one of the finest beaches in the U.S. (well, east of Hawaii anyway). I found a comfortable spot under a palmetto tree and read about the antics of a young Sir Percival trying desperately to overcome his upbringing at the hands of an overprotective mother who dressed him in lace frocks and gave him dolls to play with so he wouldn’t run away to become a knight.

Poor Sir Percival. I tried to imagine my own mother attempting to protect me from my budding manliness by sending me to school in a skirt so I wouldn’t be tempted to sign up for peewee football. Predictably, a year of peewee football was plenty enough to convince me that my interests and talents lay more in more intellectual pursuits, even without the dress. I took a moment away from my novel to close my eyes and appreciate the superiority of being raised by an open-minded woman who preferred wit to brawn but knew enough to let her kids learn things like that for themselves.

From there it was an easy leap to decide to go home for the weekend. I mean, it wasn’t like I had a hot date back in White Sands. Got to Walterboro too late for dinner, but of course Mom, thrilled to hear I was coming, had something to eat ready to pop in the microwave. In all truthfulness, it wasn’t nearly as good as Peckerwoods’. But it was home.

“More hours stolen from my life only and…”

I think you mean “only life”?

Enjoying right along.

Thanks–got that all fixed.

I like the reflection in this chapter. 🙂

Agreed. A lot of Rick to savor.

You need an accent grave on “voila” and I would not capitalize either the “La” or the “voila.” Recommend putting them in italics as a French term. The translation in French is proper “there she is” but it should not be capitalized.